Latvians are the descendants of Baltic tribes that arrived at the area ~4000 years ago, making them one of the oldest European nations in the current location. For several millennia modern-day Latvia was largely untouched by outsiders, away from the main migration and trade routes, worshiping is own gods.

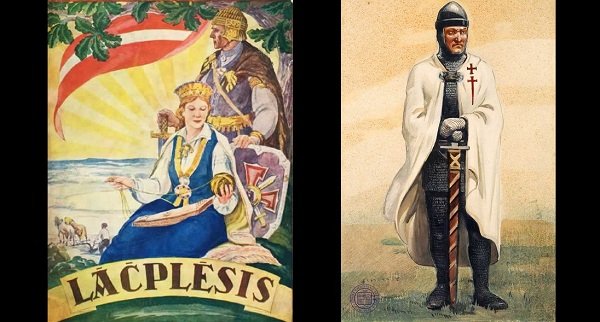

However, as the rest of Europe adopted Christianity, pagan Balts increasingly became seen as an anachronism. German crusaders came to redress this ~1200, conquering Latvians and making them adopt Catholicism.

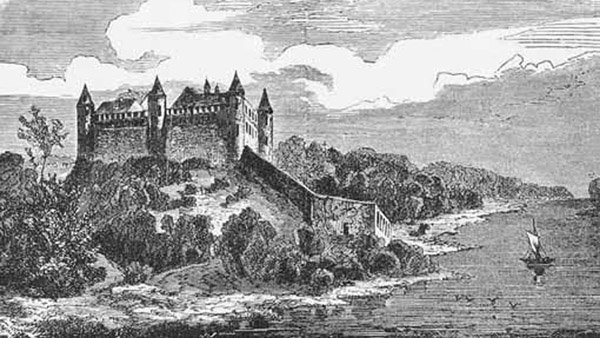

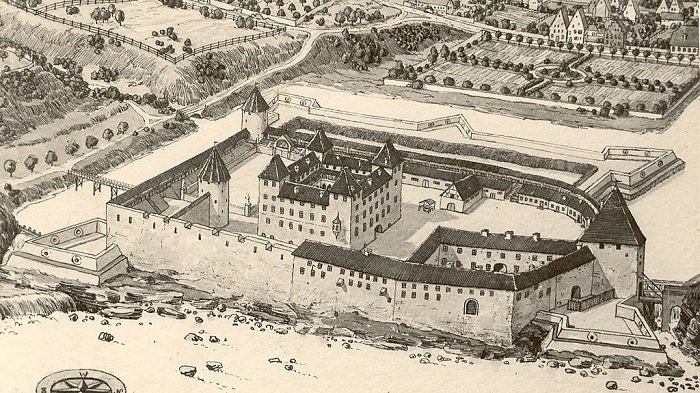

Germans remained the local overlords, establishing their theocracies such as the Livonian Order. As the entire region became Christian, these crusading statelets lost their reason to exist. With European support for crusades dwindled, Latvia was conquered by Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1562. However, even after the annexation, local Germans retained their cultural domination.

At the time Catholic Church faced a new struggle from within as the Reformation movement started. Protestant ideas became popular among Latvia’s German nobility who converted to Lutheranism. Latvian peasants generally followed suit. This was the golden age for the German-ruled Duchy of Courland-Semigallia, which despite the status of Polish-Lithuanian vassal, was rich enough to partake in the colonization of the Americas.

By the 17th century, the power of Poland-Lithuania was waning as two new regional powers were rising: Sweden and Russia. Sweden managed to capture Riga and Vidzeme (Northern Latvia) in 1621, but its greatness proved to be temporary. Russia, on the other hand, continued to dominate Eastern Europe ever since. Russians managed to conquer the whole Latvia in a series of wars between 1700 and 1795.

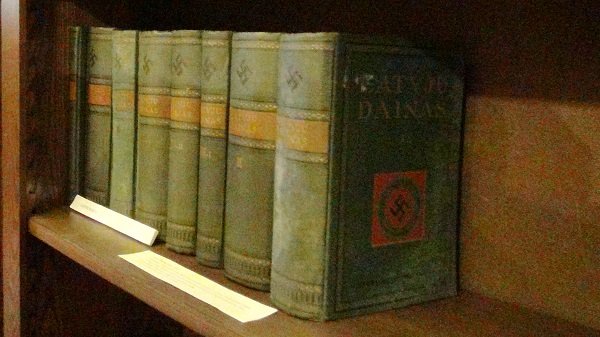

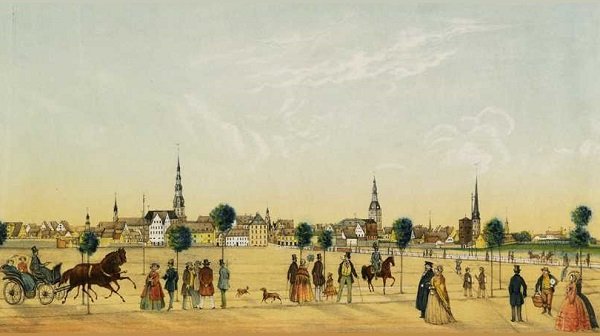

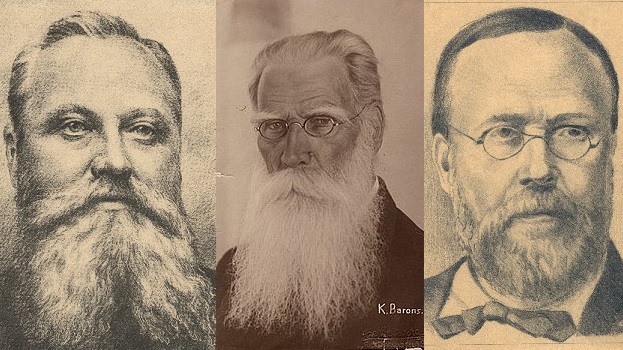

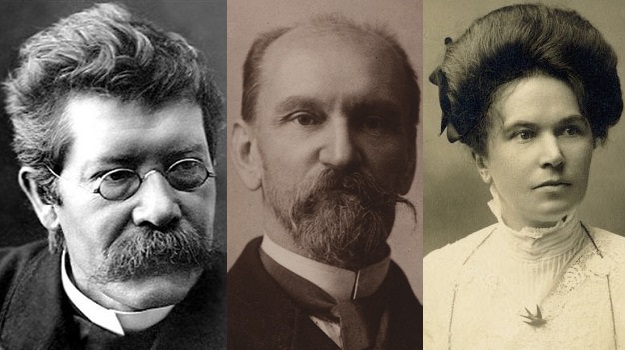

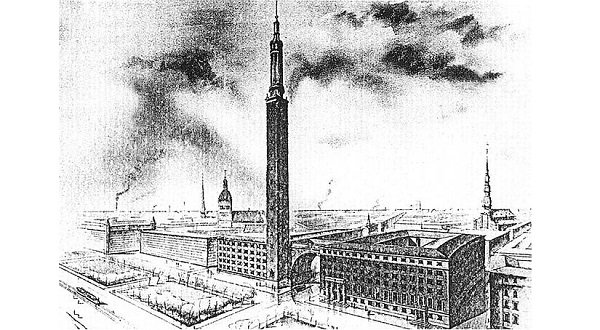

After modern technologies belatedly reached the Russian Empire, Latvia became an industrial heartland in 1860-1914, with Riga as one of the largest imperial cities. For the first time, ethnic Latvian peasants were moving to the cities in large numbers, staffing the factories. In what was known as the Latvian National Awakening some of them excelled in art, business, and urban jobs, at the same time, beginning to respect their own culture and language.

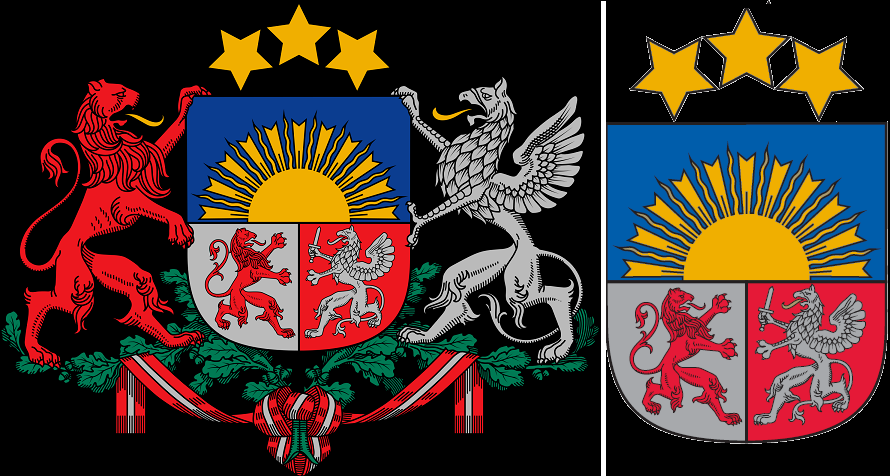

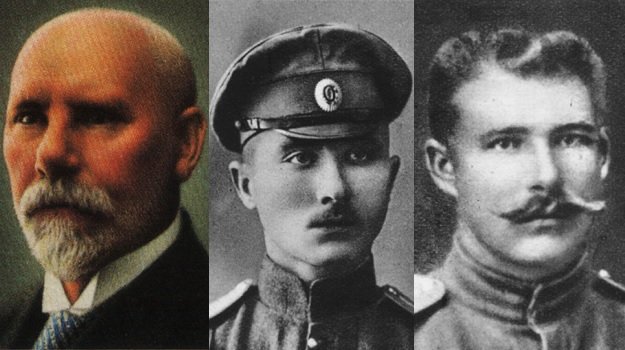

As the cities became Latvian-majority ~1890s, the Revival leaders increasingly called for independence, believing that only then would Latvian culture be sidelined by neither its Russian nor German counterparts. Freedom became possible in 1918 when both Russia and Germany lost World War 1.

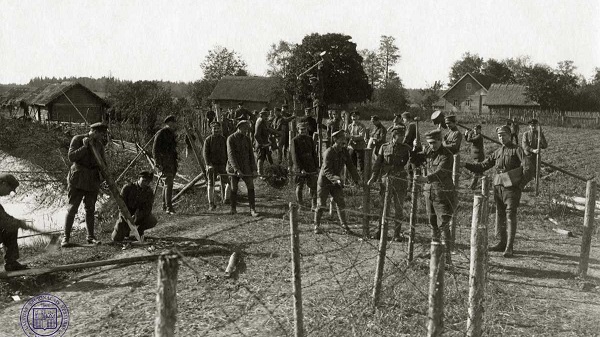

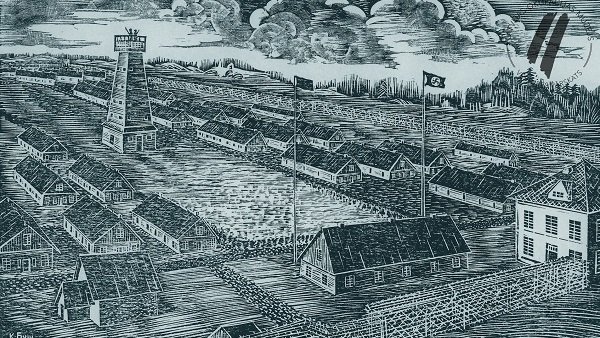

Two decades of prosperous independence followed where Latvians achieved their place among European nations. However, Russia and Germany were back in World War 2 (1940), both occupying Latvia and perpetrating genocides. The Soviet Union won the war and stayed until 1990. The occupation severely altered Latvia’s demography and held its economy decades behind the West.

In 1990, Latvians declared independence and the Soviet Union collapsed soon after. Latvia has since looked westwards to ensure its defense from any new Russian attacks.